Key Issues

Roles and Responsibilities

The Camp Management Agency’s main responsibilities in relation to participation are to:

- promote, facilitate and coordinate a participative approach among all stakeholders

- ensure equal access to participate in all camp activities for all groups

- build trust among the camp population, service providers, host community and other stakeholders

- set up leadership and representative governance structures

- promote, coordinate and set up forums for listening, dialogue, information, exchange, feedback and complaints

- involve members of the camp population as volunteers in specific tasks/projects

- promote the employment of camp and host population such as in cash-for-work initiatives related to camp activities

- encourage community participation through such groups as neighbourhood watch schemes, care groups for persons with specific needs and recreation groups, sports and celebrations

- promote and coordinate capacity building activities to prepare people for a life after camp and for durable solutions.

Degrees of Participation

The table below sets apart the different extents of participation of a camp’s population. Arranged from a high degree of participation of the displaced population, this scale is only an indicative generalisation. Participation may include a variety of activities involving the camp’s population in different ways and to various degrees. This table may be useful during planning or monitoring and evaluation as a reference of community participation in Camp Management Agency activities.

| Degree of Participation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Ownership | Communities control decision-making and other partners facilitate their ability to utilise resources. There is therefore greater ownership and a stronger sense of belonging and responsibility |

| Interactive | Communities are completely involved in decision-making with other partners. |

| Functional | Communities are involved in one or more activities, but they have limited decision making power and other partners continue to have a part to play. |

| Consultation | Communities are asked for their opinions, but they don't decide on what to do and the way to accomplish it. |

| Information Transfer | Information is gathered from communities, but they are not taking part in discussions leading to informed decisions. |

| Passive | Knowledge is shared with communities, but they have no authority on decisions and actions taken. |

The scale describes to what extent the displaced population are given a voice and power to make decisions. The Camp Management Agency and all stakeholders involved in camp community participation must be willing, able and free to relinquish supreme decision-making power. Contextual factors such as level of security, relations among groups living in the camp, donors' restrictions, time, the camp population's capacity and ability to focus on more than survival, might influence the degree of participation in the camp.

Consult and Act on!

While there may be considerable frustration if a Camp Management Agency does not consult the community, it can be even worse to consult, but then not to act on, or simply to ignore the recommendations.

Participatory Structures

There are many ways in which the Camp Management Agency can encourage and develop participation, but the most common way is through representational groups. After assessing the context and existing participatory structures, the Camp Management Agency should strive to find ways to support and further develop and/or adjust these structures to ensure that participation is as representative as possible. Members of the host community may also benefit if included in these structures.

Representative groups may take many forms and should have a significant role to play in planning, programming, monitoring and evaluating service provisions and protection. These groups may cover a number of tasks related to the camp’s communication needs and entail channelling daily challenges to the appropriate decision-making power structures. These groups may ultimately play a very important role because many issues may be solved directly through the community without bringing the problem to the camp management level.

The way the different committees and groups interact within the management structure of a camp is context specific and might depend on the camp's size, the duration of displacement, the number of stakeholders present in the camp and the composition of the displaced population. For each type of structure, the Camp Management Agency should advocate, facilitate and assist in the drafting of terms of reference and a code of conduct. The different structures might also need some support in finding necessary materials and a place to meet to fulfill their tasks.

Despite the way structures below are labelled, and as some may serve similar purposes in different camps, it is not expected that each one of them exists in all camps. The most important is that information is expressed, channelled, listened to and reacted upon.

Build Resilience!

Participatory structures can be built upon if they promote self-management and ownership in a sound way. An added value is the strengthening of resilient communities better prepared for a changing environment and life during and after displacement.

Camp Leaders

In a camp setting the population is rarely homogeneous. Displaced communities may come from different geographical locations and have various languages, religions, ethnic identity, livelihoods or occupation. Given this diversity, effective participation may become challenging to ensure representation of all and to take into account distinct aspects of each group. However, displaced communities will also share commonalities. They may for example speak the same language, belong to a similar ethnic group or lived in the same village.

Camp leaders are similarly diverse. They may derive authority from being self-appointed, from tradition or faith or they may be charismatic people who came forward when the community was in crisis. Generally, camp leaders are an important asset for a Camp Management Agency and are easily identified simply by asking the camp population. It is important to understand whom the leaders represent and whether they all have the same level of representation and authority, for example, whether they are all leaders of different villages, or claim to represent groups of villages. It is also essential that every individual in the camp be represented at some level, so gaps need to be identified, especially for groups with specific needs. Asking the leaders to draw a common map showing their various supporters or geographical areas can help clarify where there may be overlap or gaps. If they have not already organised themselves according to traditional structures, it is helpful to do this by having geographical block or sector leaders. In very large camps, it may be necessary to encourage several hierarchical tiers such as community, block and sector leaders to ensure that a Camp Management Agency may directly communicate with a manageable number of individuals who are acting as spokespersons for their constituents.

Having Representation May Not Necessarily Entail Participation

Community leadership may be a source of conflict. When leaders are not acknowledged by all groups within the camp or are perceived as non-representative, service providers and the Camp Management Agency may be seen as biased by working with them.

The Camp Management Agency should regularly assess whether the existing governance structures ensure participation and feedback of all displaced persons living in the camp. Individuals may refuse to participate or the structures in place may be an obstacle to their participation. In either case participation may become non-representative and measures to correct or improve participation are required. The Camp Management Agency should find creative ways to communicate with camp residents with due consideration to their opinions in decision-making processes.

The Camp Management Agency should not reinforce traditional roles that restrain opportunities for some individuals or clash with international protection standards. The Camp Management Agency must be careful to not impose simplified ideas of democracy and decision-making process or to redefine displaced communities. Without compromising protection standards, the Camp Management Agency should identify neutral strategies that are culturally acceptable and effective.

The Camp Management Agency may face situations where several individuals claim authority within the displaced community making it difficult to discern who should be the right interlocutor. The only alternative left is sometimes to start afresh and ask the camp population to nominate or elect their leaders. Traditional community leaders may feel threatened or undermined in situations of new leadership. Holding elections and/ or selecting those with positions of power and representation need to be handled with sensitivity, care and respect. It should be done in a way which does not exclude anyone from coming forward and volunteering for active participation. This is part of the Camp Administration’s responsibility to represent national authorities and must be supported by the Camp Management Agency if necessary. Often, assistance such as providing staff, stationery or copying facilities is sufficient to enable the holding of an election. The camp population can then choose their own representatives; ideally a man and a woman from each block or district in the camp. Elections that are well organised can make the difference when it comes to peaceful cohabitation, open communication and a protective environment in a camp.

Steps to Setting Up Participatory Structures

In order to promote participation the Camp Management Agency should assess the context and existing participatory structures, find ways to support them and further develop and/or adjust them to ensure that participation is as representative and inclusive as possible. To achieve participation, the following steps may be useful:

- assess existing participatory structures, and whether governance in place is organised to ensure participation

- support/build on relevant structures

- propose and set up missing structures.

STEP 1: Assess existing participatory structures

Structures functioning before the crisis, or which are functioning after the crisis, can be built and relied on by the Camp Management Agency. The Camp Management Agency should determine what different social and leadership structures exist in the camp, their status and how they can best be used in developing participation. Since it may influence the life of a camp, this assessment should also include structures existing within the host community.

STEP 2: Support and build on relevant structures

After assessing existing power and decision-making structures, the Camp Management Agency should support and build on structures supportive of promotion of participation in camp management. This means structures that ensure equal access to participation for all groups living in the camp and which operate in accordance with humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence.

STEP 3: Propose and set up missing structures

After assessing (step 1) and supporting and building on relevant structures (step 2), the Camp Management Agency, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders, may propose the set-up of missing structures (step 3). Such a process should be carried out in agreement and continuous dialogue with the camp population. Setting up missing structures should be recognised by the camp population as useful, relevant and helping to increase the effectiveness of equal service provision for all, including vulnerable groups.

Camp Committees

Camp committees are groups within the camp population that have a specific sector or cross-cutting focus. Camp committees are often points of contact for service providers operating in the camp and should share the resposibility for effective service provision. Examples include committees for health, waste management, water and sanitation, environment, women, children, youth and other committees representing vulnerable groups. Some of these can be difficult to form and sensitivity will be required. Members of certain groups may not wish to come forward, or members of the family or community may not see their participation as necessary or positive. The Camp Management Agency, along with other stakeholders, must ensure that these groups and individuals are appropriately represented and supported.

Many committees in a camp meet on a regular basis. Some may have technical expertise and some may be trained to carry out monitoring tasks for the service providers or the Camp Management Agency as well as representing the camp population at camp coordination meetings. These groups may then meet with other stakeholders, such as on-site national authorities, service providers, the camp manager and a host community representative. Following these meetings, the camp committees may also contribute to disseminating information to the camp population, providing feedback and following up on agreed actions.

Build on Future Generations

Youth have energy and enthusiasm, vitality and power to promote social change. With the right support youth can play a central role in contributing to the positive development of the camp community and stabilisation of the camps. Youth should be considered as a resource when developing community outreach programmes, awareness raising initiatives, care and maintenance interventions as mobilisers, peer to peer networks and incentive work.

Community Groups

Community groups are usually formed of persons who have a common characteristic, for example women, adolescents or older persons, or focus on some specific aspect of the camp life, for example security, teacher-parent liaison or water point maintenance. Community groups may be less formal than camp committees in terms of monitoring and representation duties. In large camps several community groups may exist and liaise directly with members of the camp population or with the relevant service provider by bringing particular issues to the Camp Management Agency’s attention. Community groups may sometimes be widely used and accepted as part of a community’s culture. Small group meetings are generally welcomed and seen as a positive strength in a camp environment. This is especially true in camps where social structures are lacking or disrupted, and should therefore be encouraged.

Advocacy Role

An important role of committees, working groups and taskforces is to provide a voice to those who may otherwise not be heard, to bring forward specific messages to the Camp Management Agency and stakeholders. Some committees will be able to advocate for themselves while others will seek third parties to advocate on their behalf. For certain committees, the visibility involved in participation can jeopardise their security or further increase their vulnerability or marginalisation.

Focus Groups

Focus groups are discussion groups, mainly used in participatory assessment methods which enable understanding and analysis of a certain topic. These groups are selected on the basis of a common characteristic such as gender, age or socio-economic status. Group discussions are facilitated by a member of the camp staff whose role is to gain insights from members on their experiences of a specific service or issue. The discussion is structured around a few key questions to which there are no right answers. Focus groups are especially effective because women, men, boys and girls of different ages and backgrounds are affected differently by displacement and have different needs and perceptions. Comparing the qualitative information provided by different focus groups can help to provide a balanced and representative assessment of a specific issue.

Working Groups - Task Forces

These are groups that are set up for a specific period and with a precise task or objective which is sometimes unexpected or urgent. Members of working groups or task forces will often be selected on the basis of their expertise or knowledge to compile information or to carry out a technical task. For example, due to the unexplained drop-out of teenage girls from school, a working group or task force might be set up to understand the issue and suggest solutions.

Voice From the Field - Cleaning Camps in Sri Lanka

Camps were faced with the challenge of how to deal with garbage. Camps were small and routinely littered with rubbish, only a fraction of which was collected by municipal councils. Using the Buddhist concept of shramadana (donation of work), everyone in one camp, residents, together with the Camp Management Agency, got together on a ‘clean-up day’ with tools provided by the Camp Management Agency. As a follow-up, camp committees were established to monitor and to work with private and local government service providers which are now employed to better manage garbage.

Feedback Mechanisms

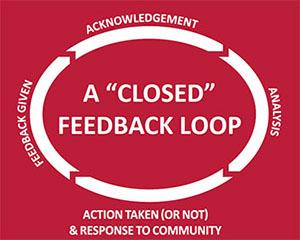

Mitigating tensions and conflicts also involves ensuring equal access to assistance and services, transparent information dissemination, clarity of procedures and complaint and feedback mechanisms. There should be follow-up by the Camp Management Agency and relevant stakeholders. The effectiveness of a feedback mechanism relies on the response given to the feedback received.

“A feedback mechanism is seen as effective if, at minimum, it supports the collection, acknowledgement, analysis and response to the feedback received, this forming a closed feedback loop. Where the feedback loop is left open, the mechanism is not fully effective.”

Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action (ALNAP), 2014. Effective Feedback in Humanitarian Context, Practitioner Guidance.

Whether it happens through camp committees, focus groups, representatives or one-on-one communication with the Camp Management Agency, it is important that the camp population has a channel to communicate feedback regarding assistance in camp. To ensure that this is done in a fair and transparent manner with equal access for all, it may be useful to set up a formal structure known by all. During the routine daily work of a Camp Management Agency, feedback may informally be received and simple issues directly resolved. Other minor issues occurring during distributions, identified during house-to-house visits or issues related to the performance of some service providers, may be brought up to the regular coordination meetings in camps. A more formal approach will request the collection, reception and responses to feedback through a dedicated structure and clear procedures. Both approaches in handling feedback have their pros and cons. The approaches used are context specific and depend on the way feedback is handled. A mixture of both informal and formal mechanisms is often used. Ideally, the feedback mechanisms should be designed with modalities and tools commonly used, preferred and understood by the actors of any specific context. The literacy rate of the camp population, the safe access to all including vulnerable groups, the confidentiality of communication support and the available resources to role out the process are elements to consider when putting in place an appropriate feedback mechanism.

Voice From the Field – a Complaint Desk During Food Distributions in Zwedru, Liberia 2013

The Camp Management Agency received many angry complaints in the aftermath of food distributions, when it often was too late to solve the problem. As a solution a complaint desk was set up where the camp population could immediately address problems around ration cards, portions and family size. This was welcomed by the camp population, and tensions decreased significantly as problems could be solved much faster than previously.

Some examples of communication tools used for informal feedback are visits, community meetings, assessment and monitoring tools, household questionnaires and post-distribution forms. Examples of communication tools used for formal feedback may be complaint committees, grievance committees, suggestion boxes, radio with call-in service, letters addressed to the Camp Management Agency, hot lines and SMS messaging or visits to the Camp Management Agency during working or predefined hours.

Grievance Committees

Grievance committees can be established in order to deal with minor disputes and violations of camp rules. Members of grievance committees should be generally respected by the camp population and elected. They may impose fines or order community work. Areas in which grievance committees can be involved must be clearly defined and the Camp Management Agency should monitor their work closely.

Feedback mechanisms may also be used to address fraud, misappropriation or abuse. It is important to develop specific procedures ensuring anonymity and confidentiality when doing so. Follow-up and referral procedures of sensitive issues such as sexual exploitation and abuse should be the responsibility of the relevant sector agency.

☞ For more information on sexual exploitation and abuse, see Chapter 2, Roles and Responsibilities.

Through formal and informal channels different types of feedback may be brought to the Camp Management Agency's attention. It is important to distinguish between feedback related to day-to day activities, usually related to the existing assistance modalities (for example targeted criteria, preferred assistance options, schedule for distribution) and the ones related to a broader level of the humanitarian response. For the former the Camp Management Agency will work closely with the other stakeholders to address the issues. Advocacy and consultation with the Cluster/Sector Lead and the national authorities will be required in the second case.

The Camp Management Agency should coordinate and harmonise the different formal and informal feedback mechanisms avoiding duplications and promoting their establishment when none exists. Above all, the Camp Management Agency should advocate for an informed decision-making process for all feedback mechanisms and ensure that it becomes a continuous learning process for all stakeholders.

Capacity Building

The capacity to participate in decision-making processes increases if community representatives and members acquire the necessary knowledge and experience of technical sectors and camp management. Building capacity can be done through awareness programmes, training and coaching which addresses different topics relevant to the empowerment of the camp population. These capacity building activities can be carried out by service providers or the Camp Management Agency according to needs, resources and agreements in place between the different stakeholders. The Camp Management Agency needs to coordinate these different activities and to advocate filling gaps. The Camp Management Agency should place particular emphasis on building the capacity of existing participatory structures by ensuring that individuals engaged in them all acquire the necessary skills to play a crucial role in the management of the camp.

Awareness Programmes

Awareness programmes are usually organised on issues related to the social and physical wellbeing of the camp community. It is common to launch health, safety and protection programmes for the camp population and to alert them of their rights and responsibilities. The Camp Management Agency may propose, for example, awareness campaigns to sensitise the camp population on the importance of community-based initiatives, the role of participatory structures, and the function of terms of reference and of codes of conduct for members of committees.

Training

Training is usually carried out for specific skills in order to sharpen existing talents within the camp. The Camp Management Agency may propose a training targeting leaders, committees' or groups' members to address camp governance issues such us roles and responsibilities in camp management, leadership, anti-corruption, coordination, communication techniques, participatory methodologies, international standards and camp maintenance. Service providers may initiate technical training related to specific sectors which are deemed crucial. This may range from accounting to sanitation maintenance. The Camp Management Agency should liaise with other service providers or agencies to make additional training available where needed and/or appropriate.

Voice From the Field - Remunerated Versus Unremunerated Training in IDP Camps, Puntland, Somalia 2013

IDPs insisted on being paid to attend the agency’s training, claiming that they would otherwise have had to stay away from their normal jobs and miss income for the training period.

There was no history of providing training in these camps, and the agency had no budget to pay the trainees. In any case, the agency thought that paying for IDPs to attend the training would indicate tacit acceptance of the fact that community members have little genuine interest in learning anything. The lack of funding was explained to the community leaders and the question was posed: “When you send your children to school, do you ask the school to pay you, or do you, as a parent, pay the school for teaching your children?”.

That was the end of the discussion. Much training was delivered to IDPs in several camps of the region, with no remuneration.

Coaching

Coaching can be an effective way of following up on training, to provide ongoing support and guidance for individuals or groups within the camp or host communities who are developing new skills or carrying out specific activities within the camp. Coaching will be conducted by the Camp Management Agency or the service providers according to the agreed responsibilities regarding capacity building. The Camp Management Agency can use coaching to support camp committees' and groups' members to find community-based solutions to identified problems. As well as for all other aspects of participation, the Camp Management Agency should promote and advocate for continuous follow-up of all capacity building activities conducted in the camp.

Voice From the Field - Camp Management Coaching, Dadaab, Kenya 2013

Coaching was introduced when several community representatives wanted to be further engaged after completing the standard camp management training designed to provide participants with the knowledge and the tools necessary to manage certain camp activities for themselves. The camp management coaching was provided to follow-up camp management training in order to bolster the technical knowledge, skills and attitudes the camp community members acquired through the training sessions.

Several coaching groups were formed addressing different aspects of camp management such as roles and responsibilities, distribution of various items, gender-based violence (GBV) and site planning. The coaching groups had weekly or bi-weekly sessions facilitated by camp management trainers. During the coaching sessions and with the facilitator’s support, the participants discussed gaps related to specific sectors and formulated community-based solutions. The camp management trainers continued to assist during the implementation of the community-based initiatives.

This activity was a long-term approach lasting three years with the aim of cultivating community initiatives and establishing new social patterns of conduct. The target groups became proactive and competent practitioners of camp management. Their expertise had a positive impact on standards of living in the camp.

Aims and examples of capacity building programmes are presented in the following table.

Capacity Building Programmes

| Programme | Aim And Examples | Target Group |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness |

Aim: to improve knowledge and raise alertness in relation to issues affecting camp population Examples: awareness campaigns regarding camp regulations, importance of participation, use of Code of Conduct and terms of reference for participatory structures |

Camp population, host population, national authorities |

| Training |

Aim: to build or improve competencies in camp management and related topics Examples: training sessions on camp management, peaceful cohabitation, anti-corruption, leadership, communication, participatory techniques |

Camp population, host population, national authorities |

| Coaching |

Aim: to enable community members and representatives to identify and analyse problems and develop community-based solutions Example: coaching sessions on camp management issues such as community protection monitoring, safety and security, registration, book-keeping, service provision, warehouse management and filing system. |

Camp management staff, camp committees, services providers, national authorities |

Other Considerations

Coping Mechanisms

Coping mechanisms are adaptive strategies or responses that are used by members of the displaced communities to deal with changes and stress and to solve problems. The Camp Management Agency must assess, in close collaboration with specialised actors, the camp population’s own coping mechanisms and support these if they are sound and constructive. This assessment could be done through focus groups, informal talks, surveys and key informant interviews.

Conflict Management

Camp Management Agencies must be prepared to manage tensions, disagreements and conflicts and to empower their staff to deal with them effectively, as part of their participation strategy. This may include providing training for staff and camp populations in effective communication skills, including non-violent communication. It can also entail being trained in conflict mediation and management; using and enforcing codes of conduct; following up complaints and the use of procedures to remove or replace members in groups. It will also involve security procedures that can be implemented to keep people safe if a situation gets out of hand.

Traditional Conflict Resolution Strategy

In many communities there are traditional conflict resolution strategies and mechanisms. Elders may sometimes intervene to resolve certain conflicts within a community. When defining which issues such conflict resolution mechanisms can deal with, it is important to note whether these are respected by all and to what extent they also represent for example women, and the most vulnerable. It is also important to understand to what extent the values of various groups correspond or agree with local legislation, human rights and international laws.

Traditional conflict resolution mechanisms are often useful for:

- solving internal conflicts peacefully

- creating peace-building initiatives

- representing groups and communities

- clarifying codes of conduct, camp rules and sanctions for infractions.

Involving Women

Understanding the protection needs of women and involving them in planning, design and decision-making can prevent many protection-related problems. Whilst it is sometimes complicated and challenging, involving women is not always as difficult as it is said to be. Even in male dominated societies where women are not in the public arena they are often key decision-makers within the household. Humanitarian actors can support women’s participation by focusing on issues around household concerns and the influence of the domestic arena. Strategies to effectively involve women can make use of their specific social position and existing cultural roles rather than trying to involve them in ways which go against tradition.

Choices Of Strategies

Camp Management Agencies need to be cautious, however, that strategies chosen do not result in female repression being condoned, supported or reinforced. They must be aware that displacement, violence and conflict may sharpen the differences and the tensions and inequalities between genders.

Constraints on women’s participation may in part be due to the many time-consuming household tasks that are culturally seen as a woman’s responsibility. Displaced women often have backbreaking responsibilities in caring for family members and lack the time needed for other activities. Any type of participation initiative, therefore, must be thoroughly planned to take into account the daily realities of people’s lives, their aspirations and others expectations. Goals, objectives, potential constraints, additional support and follow up should all be given due attention. Examples of additional support are child-care schemes and, as appropriate and feasible, encouraging the sharing of domestic chores.

Employment

The Camp Management Agency and the service providers usually need workforces to accomplish certain tasks in the camp. Although employment, paid or unpaid, is not an example of direct participation, it can have an influence in defining programmes and decision-making. Stakeholders implementing technical programmes will seek teachers, engineers, health workers or construction workers, for example, while humanitarian actors will require support staff such as administrators, translators, accountants, logisticians and warehouse employees. The Camp Management Agency should seek and identify individuals with the professional skills that are needed. Information about education levels and professions of the camp residents is often gathered during registration.

Deciding on which type of jobs should be remunerated can be a source of great friction. When it comes to participation in camp committees, such as teacher-parent associations or child welfare associations, working on a voluntary basis may seem more acceptable. However, opinions on paid and unpaid work are highly context-specific. The Camp Management Agency needs to carefully consider a common strategy among all stakeholders in the camp. There are a wide range of jobs where workers may either earn a salary, receive compensation or be mobilised on a voluntary basis. Several factors should be considered before deciding to offer paid jobs. It may be justified to pay someone who is working full time, meaning this person will not have sufficient time to earn money elsewhere to support family members. Work which serves a wider interest such as cleaning latrines in a marketplace, may justifiably be remunerated while someone cleaning latrines in dwelling blocks may not. It is important to consider the risks taken by the employee and whether offering paid work will reduce susceptibility to solicit or accept bribes.

In situations where labour is paid, the Camp Management Agency should ensure all service providers harmonise salaries of paid employees and stipends given for volunteer work.

There should be agreement on which kinds of employment will be paid/compensated and which will not, early on in the life of the camp.

Building Relationships With Host Populations

Competition over resources and neglecting local needs may increase friction between camp residents and local populations. The Camp Management Agency plays an intermediary role between the displaced population and local communities and should be proactive in identifying factors which may give rise to increased tension and work with both communities to find solutions.

Assessing local needs is especially important in situations where local communities are themselves impoverished or affected by the conflict or the disaster. In some cases it may be that the host community has lower standards of living than the camp population. They may feel threatened by the presence of the camp, aggrieved that camp residents compete for access to firewood, land, water and employment. The host population may have concerns about the behaviour of camp residents who leave the camp, especially if they are associated with, or are thought to be linked to, armed groups. Local men may be worried if women and children mix with camp residents, fearing threats to their culture, religion, life-style and/or language.

Addressing such tensions between local and displaced communities touches on many different aspects and requires an inter-agency approach. The Camp Management Agency should establish contacts between the camp population and the host community and ensure that host population representatives are consulted and attend the camp coordination meetings. Possible ways to build relationships include:

- advocating for service providers to assist the host population with community projects

- conducting social events for both host and camp communities

- organising common initiatives to protect the surrounding environment

- organising training on IDPs’ and refugees' rights and about camp management

- employing (or advocating for their employment) host community members

- hiring contractors from the host community.

A proportion of employment opportunities should ideally be open to the host community. These initiatives may offer financial support to members of the host community and also help to mitigate tensions that may occur between both communities.

Voice From the Field – Inclusion of Host Community, Somali Refugee Camps, Kenya 2013

Supported by a humanitarian shelter agency, refugees were using soil to fabricate mud-bricks to build their houses. During coordination and ad hoc meetings the host community complained that the land was starting to resemble lunar and craters and threatened to stop a housing project. The role of the agency was crucial: to take the time to understand the real concern of the host community and to appreciate that town residents, not being helped by the agency, had living conditions which were almost as bad. The host community could not see what benefits humanitarian actors brought for then. In the dialogue between the Camp Management Agency, host community and service providers the idea emerged of using local contractors to dig water reservoirs in planned areas outside the camps. From these reservoirs, the soil for the refugee mud-bricks was extracted. Filled with water during the rainy season, the reservoirs provided the host community with water for irrigation and watering cattle during the dry season.

Importance of Interpersonal Skills

Dialogue and exchange between the camp management staff and the camp population are central to any participatory approach. These must be based on respectful communication, transparency and appropriate attitudes, behavior and consideration for customs and beliefs of the camp population. The Camp Management Agency should seek national and international staff members who possess a wide a range of interpersonal skills, including listening, communication, facilitation, conflict management, participatory methods and collaborative problem solving. Staff need to be supported with ongoing supervision, training and coaching.

Participatory Learning and Action Approach

Participatory Learning and Action (PLA) is an approach for learning about and engaging with communities. PLA originated in East Africa and India and is now applied in many countries and in a variety of circumstances. It includes approaches and methods for enabling communities to do their own assessments, analysis and planning and to take action to solve challenges.

The approach can be used in identifying needs, planning, monitoring or evaluating projects and offer the opportunity to go beyond mere consultation and promote active participation.

It has been used, traditionally, with rural communities, but it can be a useful guidance for the camp management staff to convene meetings and focus groups. The Camp Management Agency may consider training staff working in close contact with the camp population on PLA methodologies.

Challenges in Participation

Participation is one of the foundations of camp management. Below are the challenges and mitigation measures the Camp Management Agency might face during a camp’s life cycle.

Perceptions of Participation

The dynamics of a participatory structure are usually determined by culture, beliefs, norms, values and power relationships. Humanitarian actors sometimes make the mistake of assuming that participation is automatically viewed as a good thing by all. While they may want to implement an equitable and inclusive approach, this may not be the norm for many cultures. It is therefore essential that the Camp Management Agency understand the context sufficiently to find a balance between respecting cultural sensitivities and giving a voice to the voiceless. The camp residents and the Camp Management Agency may have unrealistic expectations from participatory initiatives. These expectations need to be clear, shared and agreed upon by the displaced population, the Camp Management Agency and other stakeholders working in the camp. Open dialogue should be implemented from the onset of the camp response. The Camp Management Agency should ensure there is space to continuously discuss participation issues among all stakeholders.

Time and Resources

Personal behaviour, communication style and the skills of the Camp Management Agency staff will significantly impact the extent of the camp population’s involvement. The Camp Management Agency should therefore commit to providing long-term and continuous supervision and guidance to its staff as well as all needed time and resources.

Participation in First Emergency Response

On one hand working with participatory structures is a long-term process. On the other, involving the population in responding to rapid onset disasters may slow down emergency and life saving interventions. The Camp Management Agency may sometimes find itself in a position of taking decisions without the entire participation of the camp residents, especially when lives are at stake. A fine balance needs to be struck and the Camp Management Agency will sometimes react urgently and decide with a small group of persons, while always being aware of the need for greater and more inclusive participation.

Replicability

Participatory structures are very context specific. One successful participatory approach may not be replicable in another context. The Camp Management Agency must strive to understand the situation's dynamics and the local culture to effectively seek the participation of the camp residents. This requires extensive dialogue and close collaboration with the camp population, host community and national authorities at the onset of an emergency.

Transparency

Transparent communication with the camp population is a pillar for effective community participation. Consulting and engaging the camp population may sometimes put camp management staff and camp residents at risk. Sharing information may lead to diversion of assistance for non-humanitarian purposes.

The security of staff and camp population remains paramount and the Camp Management Agency must take security issues into account during their initial assessments and define a common strategy around humanitarian interventions with all stakeholders. If security risks are identified, a common strategy around humanitarian intervention must be developed with all stakeholders.

Misuse of Participation

Misuse of funds and assets, the diversion of assistance, and manipulation of information, are real risks in any humanitarian endeavour. Staff recruited from the displaced community may be under daily pressure from their peers. In particular, staff involved in registration and distribution may face many challenges and find it hard to resist bribes or coercion from relatives, friends or community leaders. Leaders or community representatives may use the participatory structures established in camps for personal gain or to obtain advantages for their family or ethnic group. There are no quick-fix solutions to address or mitigate these risks. However, working transparently, rotating staff and establishing clear terms of references, codes of conduct and job descriptions for both staff and community members, can help. Agencies should recruit from all groups, including the host population, and closely monitor the work, implement efficient complaints mechanisms, and acknowledge and reward high standards of integrity.

Camp Population Motivation

Long term dependency on assistance, traumas due to displacement and low self-esteem might impact voluntary involvement in camp activities. The Camp Management Agency may implement awareness programmes in collaboration with actors in appropriate participatory structures to highlight the fact that the camp population’s participation may have a positive impact and improve living conditions in camps. The modalities of participation should be agreed and coordinated with all stakeholders.

Multiple Approaches to Participation

Stakeholders intervening in a camp might have different participatory approaches and strategies. A mix of differing organisational policies, internal experiences, funding or personalities may confuse and create tensions within the camp population. The Camp Management Agency should initiate a dialogue with all relevant stakeholders to promote a common approach with the camp community and initiate forums for sharing best practices and lessons learnt.